Current Questions and a Theology of Vaccination

The number of times my patients’ parents ask me questions about vaccines each day has skyrocketed. The increase seems prompted by the appointment of new government leaders who are unearthing old questions about vaccines and the current measles outbreak in parts of our country. The questions typically reflect one of two different fears. Some parents want to know if vaccines will harm their children, and others fear that some vaccines will not be available when their children need them. Both are good questions from parents who want to do the right thing for their children.

In this post, I will address these questions from the perspectives of science and theology. I am a pediatrician who has been in private practice since 1997. I’m a parent of two daughters. My wife and I had to make decisions about vaccinating my daughters, including decisions about new vaccines that became available when they were very young. I am also a theologian, and I recently successfully defended my doctoral dissertation, which focuses on the intersection of science, parenting, and theology and is titled “Open and Relational Parenting.”

I usually avoid writing about current issues in the news or politics. However, recent political comments around vaccines affect my patients’ families and must be addressed. I was further prompted to write about this issue by a recent post by a friend and graduate of my seminary program, John Pohl. John is a pediatric gastroenterologist who also holds a doctorate in theology. His recent post, “Vaccines are Good and Evolution is Still True: A Religious Perspective,” tackles some of these issues from his vantage point.

Parents who ask questions about vaccines’ safety, effectiveness, and availability do so because they love their children and want to make good decisions on their behalf. They don’t typically come waving political flags or hats and aren’t trying to make a political point through their questions. However, they have often heard family members, politicians, news, or social media raise questions about vaccines for political purposes. They frequently start their question by saying, “I’m not anti-vax, but…” If you’re a parent who has questions, don’t worry. I get it. Being a parent is hard, especially when you are bombarded with conflicting information and are responsible for making the right decision for your tiny human.

There is a lot of information about vaccines, and I can’t cover all of the issues here. I will start by answering some of the most common questions about vaccines I have heard recently. After answering these questions, I will turn to theology and propose some elements of a theology of vaccination.

Vaccine Safety

Does the MMR vaccine cause autism?

Questions about the MMR (measles, mumps, rubella) vaccine and autism arose in the late 1990s and were championed by Dr. Andrew Wakefield. His primary study appeared in The Lancet in 19981. Wakefield and his colleagues’ report included twelve children who had autism or a similar disorder and had a variety of types of intestinal inflammation. Their study was not designed to evaluate MMR as a potential cause of autism and found no connection between the two. In the published paper, the authors wrote, “We did not prove an association between measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine and the syndrome described.” Despite this statement, the paper concluded, “In most cases, onset of symptoms was after measles, mumps, and rubella immunisation [sic]. Further investigations are needed to examine this syndrome and its possible relation to this vaccine.”

The scientific community has strongly criticized the Wakefield study for its recruitment of patients, uncontrolled design, and speculative conclusions. Ten of the original twelve study authors published a retraction of their data interpretation in 20042, which was followed by The Lancet’s complete retraction of the paper in 2010.3 Ultimately, the British Medical Journal criticized the Wakefield study as fraudulent.

Because the scientific community is curious, it wanted to test Wakefield’s implication that the MMR vaccine was associated with autism. Since that study, many studies designed to evaluate this possible connection have been published. These studies were performed across the globe, including the US, the UK, Canada, Denmark, and Japan. None of them found a connection between the MMR vaccine and autism. Dr. Sanjay Gupta, a neurosurgeon and medical correspondent for CNN, reviewed these studies in 2014 and summarized them, saying, “Studies, including a meta-analysis of 1.2 million children in 2014, show no link between vaccines and autism. That is not a matter of opinion. It is a matter of fact.”4 A comprehensive bibliography that includes 27 different studies is available at immunize.org, a website designed to provide vaccine information to healthcare providers.5

Dr. Wakefield’s 12-patient study has been discredited and retracted because it failed to withstand scientific scrutiny. Numerous significantly larger studies have followed it that find no connection between the MMR vaccine and autism.

Do heavy metals like mercury or aluminum that are found in vaccines cause autism?

Over several decades, various questions have arisen about the safety of mercury and aluminum in vaccines. Although both elements are heavy metals, they have been used in vaccines for different reasons and must be considered separately.

When vaccines were developed in the early twentieth century, one of the biggest challenges was bacterial contamination, which led to infectious complications associated with them. Preservatives were needed to prevent these serious complications. Several options were explored, and thimerosal was found to be the safest option at the time. It is an organic molecule containing mercury, works as an effective antimicrobial agent, and was used in some vaccines. Questions about potential neurotoxicity and thimerosal arose in the 1970s, but at that time, the low level of exposure through vaccines was considered safe.

In the 1980s and 1990s, several vaccines were added to the recommended childhood immunization schedule. With these additions, the amount of mercury a child would receive through vaccinations approached levels that the Environmental Protection Agency considered potentially harmful. In response to these concerns, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) released a statement in July 1999 encouraging the removal of thimerosal from vaccines.6 In 2001, thimerosal was removed from all childhood vaccines except for multidose vials of the seasonal flu vaccine. A thimerosal-free version of the flu vaccine has been available since 2004.

Several studies were published in the 2000s that explored thimerosal as a potential cause or contributor to the development of autism. None of these studies found a link between the two.7 Perhaps the most significant test of any possible connection between mercury in thimerosal and autism is the observation of the rate of autism after it was removed from vaccines in 2001. The CDC reports that in 2000, the prevalence of autism was 1 in 150 and increased to 1 in 36 by 2020.8 It is not known what has driven this rise, but clearly, the removal of mercury and thimerosal from vaccines did not decrease the rate of autism. If they had not been removed, other problems might have arisen. Since vaccines no longer contain mercury, any controversy about it and autism was laid to rest decades ago.

In contrast to mercury, which was used in vaccines as a preservative, aluminum is used as an adjuvant, which boosts the body’s immune response to vaccines. As an adjuvant, aluminum helps the body build immunity with fewer or lower antigen doses, reducing antigen-related side effects.

Several studies have found elevated levels of aluminum in the brains of people with autism. Current research has not identified a link between aluminum exposure and autism. We do not know why these individuals have elevated aluminum levels. It is also unclear whether aluminum contributes to autism or if autism causes aluminum to accumulate differently in the brain.

Regardless of the connection between aluminum in the brain and autism, vaccines are a minor source of aluminum exposure. For example, by their first birthday, infants in my practice receive the same amount of aluminum from vaccines as when nursing for a month or taking formula for a week. Aluminum is also present in most foods, water, and even air. When inhaled or ingested, less aluminum is absorbed compared to when it is injected. However, exposure to aluminum from other sources far exceeds that from vaccines. One study shows that exposures from these sources result in varying levels of aluminum found in young children’s hair and blood samples. However, it finds no connection between a child’s immunization history and aluminum levels.9

Aluminum adjuvants are essential to vaccines and contribute very little to a child’s overall exposure to aluminum.

It seems that the US Government supports vaccine manufacturers. Does it respond to problems with vaccines when they are reported?

Parents sometimes have concerns over the integrity of vaccine safety monitoring programs. They fear that the government is more interested in the success of “big pharma” than vaccine safety. The United States government primarily monitors vaccine safety through the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS). Patients and healthcare providers can report possible adverse events related to vaccines. These reports have led to recalls of specific vaccine lots and, in at least one case, the removal of a vaccine from the market.

The Rotashield vaccine was licensed in the United States in August 1998. It was the first vaccine against rotavirus, which can cause severe diarrhea in infants that often requires hospitalization. Ten months after its release, fifteen cases of intussusception were reported to the VAERS system with concern that they were related to the vaccine. Intussusception is a serious condition where part of the intestine folds inside another part, like a telescope. It can lead to intestinal blockage and death of intestinal tissue. Statistical analysis found that these fifteen cases of intussusception were not significantly more than should have occurred for other causes. However, in July 1999, the CDC recommended pausing the administration of Rotashield and asked providers to report any cases of intussusception that may have been related to the vaccine. Based on other cases reported in the following months, the CDC withdrew its recommendation of Rotashield, and on October 15, 1999, the manufacturer withdrew it from the market.10 After its withdrawal, researchers worked to create safer vaccines to prevent rotaviral illnesses. As a result of their efforts, two different vaccines against rotavirus were licensed in 2006 and 2008. These vaccines have been monitored closely and found not to increase a child’s chance of developing intussusception.

These events happened during my first few years in practice. When Rotashield was released, I watched the data closely before recommending it to my patients. I regularly saw information from the CDC and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) through 1999 and witnessed the system identify a problem with a vaccine that led to its withdrawal.

Of course, it is ideal if vaccines never hit the market that may cause injury. Unfortunately, pre-market studies in this case didn’t identify the risk. Thankfully, close monitoring in the months following Rotashield’s release led to its withdrawal and ultimate replacement with a safer vaccine.

The government and vaccine industry monitor vaccines for safety and potential complications even after vaccines are approved and recommended for use. Seeing this process work in the case of the Rotashield vaccine showed me that these monitoring systems work.

Kids today get many more vaccines than we did in the “old days.” Could the increase in the number of vaccines cause autism?

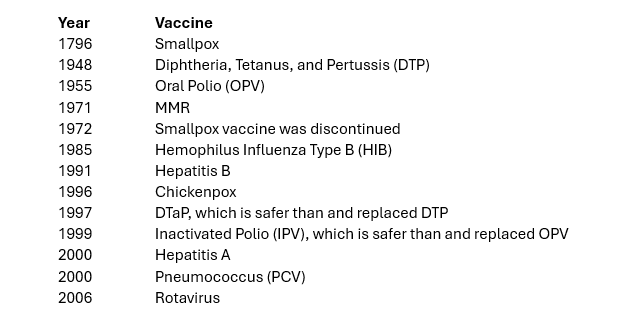

The number of childhood vaccines has significantly increased since I was a child in the late ’60s and early ’70s. When parents ask about these additions, they are often surprised that the early childhood immunization schedule has changed very little in the last two decades. Here is a timeline that gives details on when vaccines were added (and removed) from the recommended schedule:

The adolescent vaccine schedule has evolved since 2006 and includes human papillomavirus (HPV) and various strains of meningococcus. No significant changes have been made to the early childhood vaccination schedule since 2006.

The most significant changes in early childhood vaccination schedules occurred between 1985 and 2000. During this period, vaccines against five diseases were added. With each of these additions, many severe illnesses and deaths were prevented. Taking the bacterial infection Hemophilus Influenza Type B (HIB) as an example, in the US, the rate of severe disease due to HIB fell by 99% from the vaccine’s introduction in 1985 until 2000. It is estimated that from 2011 to 2020, the HIB vaccine prevented 1.4 million deaths worldwide.11

Six vaccines were added to the early childhood vaccination schedule between 1985 and 2006. Because of these vaccines, I have personally seen a significant decline in infections that cause hospitalization, severe injury, and death during my career.

When the number of recommended vaccines increases, watching for patterns pointing to potential vaccine-related injury is essential. Some people point to the rise in the rate of autism and speculate its connection to vaccines. However, the timing of new vaccine introductions doesn’t line up with the change in autism diagnosis. In 2006, 9 in 1000 children had autism. By 2020, this number had increased to 27.6 in 1000.12 In other words, the rate of autism continues to rise even though no new early childhood vaccines have been introduced since 2006.

The addition of early childhood vaccines between 1985 and 2006 has prevented significant illness and death. The rate of autism rose during those years and has continued to rise since 2006 despite no new vaccine recommendations for young children. The number of autism diagnoses continues to increase; however, this is not due to vaccines.

Vaccine Availability

Will vaccines be available for my children when they need them? Can they receive vaccines early in case they become unavailable or if there is an outbreak?

The other type of question that parents ask much more commonly these days stems from fears that the new government healthcare leadership believes vaccines are harmful and may limit their availability. People wonder if vaccines will continue to be required and if they will remain available. Politicians make promises and break promises. It is impossible to answer these questions, and parents are right to raise these concerns. My best guess is that vaccines will be required in fewer situations but will still be available.

Parents ask if their children can receive the MMR vaccine early, considering our country’s current situation with an expanding measles outbreak. Two doses of the MMR vaccine are recommended: one between twelve to fifteen months and the second between four and six years of age. One dose protects 92% of recipients, while a second dose increases that number to 97%. When children are at risk of exposure, the schedule can be accelerated. A dose can be given between six and twelve months, providing short-term protection until the child receives the other two doses later. The second dose of MMR can be given as early as 28 days after the first dose.

Some parents have concerns about the long-term availability of the human papillomavirus vaccine (HPV). HPV was released in 2006 and targets the human papillomavirus, which causes about 36,000 cases of cancer in men and women each year.13 It can prevent 90% of these cancers, and since its introduction, HPV related precancerous lesions, cancers, and deaths have drastically fallen.14 Although the HPV vaccine series is routinely recommended to start between eleven and twelve years of age, it can begin as early as age nine.

Some other vaccines can be given outside of their typical recommended schedule. Decisions about early vaccination depend on many factors. Your child’s pediatrician can be a helpful resource in this process.

A Theology of Vaccination

I approach theology from an open and relational perspective. I think of God as a spirit of love who guides us toward divine aspirations that lead to overall well-being. Since God is present with us and leads us moment by moment into the future, this theology is open. Since God interacts with all of us simultaneously, it is relational. It affirms that God’s essence is love, which Tom Oord defines as “acting intentionally, in relational response to God and others, to promote overall well-being.”15

A theology of vaccination must start with the idea of overall well-being. Actions that promote health and reduce suffering and death work toward overall well-being, perhaps especially when they involve children. In pediatrics, antibiotics, other medications, and cancer treatments can lead to overall well-being. If they are used indiscriminately without careful consideration, they can also lead to ill-being. The same is true for vaccines.

Vaccines have prevented many illnesses, hospitalizations, and deaths. In the last 50 years, 154 million deaths have been prevented by vaccines. Since many children were spared, 1.2 billion years of human life were saved.16 The prevention of such a large number of deaths and even more illnesses and suffering has improved overall well-being.

Despite this massive demonstration of good that can come from vaccines, we can’t use this information to consider all vaccines as tools of well-being. In the prior section of this essay, I recounted the story of Rotashield, a vaccine withdrawn months after its release because it caused more ill-being than good. Each vaccination recommendation must be monitored to ensure it supports well-being.

An interesting idea connected to herd immunity arises when considering overall well-being and vaccination. Herd immunity develops when enough of a population is immune to a disease that it is hard for the infection to spread. When there is herd immunity, the unvaccinated are protected by the fact that others are vaccinated. For example, if I vaccinate my children against measles, I contribute to the overall immunity of the “herd” and protect people who are not immune. In this example, my children’s vaccination and immunity to measles help protect a nine-month-old baby for whom the MMR vaccine is not yet recommended. Perhaps ironically, my children’s vaccination also helps protect another child who wasn’t vaccinated because of parental choice.

Herd immunity is lost if the unvaccinated group grows too large, and the non-immune are no longer protected. In this situation, babies who are too young to receive particular vaccines are at risk, unvaccinated children are at risk, and anyone whose vaccine wasn’t 100% effective is at risk. Vaccinating your children is an interesting example of what it means to contribute to overall well-being. When we decide to vaccinate our children, we accept likely transient pain and extremely unlikely complications in exchange for protecting our children from particular diseases. Through this process, we also help protect children who are too young for specific vaccines, people who don’t respond to vaccines, and people who choose not to vaccinate.

Vaccinations lead to overall well-being.

A theology of vaccination must also be relational. If love involves a “relational response to God and others,” we must exemplify such a response when discussing vaccines. Unfortunately, vaccination issues have become politicized, and political issues are most often cold, heartless, and the opposite of relational. Parents who ask questions about vaccines are most often overwhelmed and confused by the input they receive from their family, friends, social media, and politicians. Most of the time, they want well-being for their children, and they look for information to help them know what is in their children’s best interest. It is essential to approach conversations with parents about vaccines in the context of a relationship, recognizing the concern they have for their children and the fear that may have been handed to them by others.

God constantly guides us toward divine aspirations for overall well-being. We can better follow those aspirations when we pay attention and look for them. They can come as a “still, small voice,” the mystical experience of a burning bush, or a seemingly dull scientific study pointing to a new way to prevent suffering and save lives. Edward Jenner followed divine aspirations in 1796 when he decided to try inoculating an eight-year-old boy with pus from a cowpox sore on the hand of a local milkmaid. He recognized God’s co-creative hand in discovering the first vaccine that eventually led to the eradication of smallpox. He said, “I am not surprised that men are not grateful to me; but I wonder that they are not grateful to God for the good which He has made me the instrument of conveying to my fellow creatures.”17

A theology of vaccination says that God leads all of creation toward overall well-being. Edward Jenner recognized this when he created the first vaccine. Vaccines have prevented much suffering and saved millions of lives, but they are not perfect and require monitoring to ensure safety. Current vaccinations are well-studied and safe but require careful monitoring. When we, as healthcare providers, discuss vaccines with parents, we must think about their love for their children and the many voices in their ears. We must approach them with love and challenge them to seek divine aspirations for overall well-being as they guide and empower their children.

- AJ Wakefield, et al., “RETRACTED: Ileal-Lymphoid-Nodular Hyperplasia, Non-Specific Colitis, and Pervasive Developmental Disorder in Children,” The Lancet 351, no. 9103 (February 24, 1998): 637–41.

↩︎ - SH Murch et al., “Retraction of an Interpretation,” The Lancet 363, no. 9411 (March 6, 2004): 750.

↩︎ - The Editors of The Lancet, “Retraction—Ileal-Lymphoid-Nodular Hyperplasia, Non-Specific Colitis, and Pervasive Developmental Disorder in Children,” The Lancet 375, no. 9713 (February 2, 2010): 445.

↩︎ - Sanjay Gupta, “Dr. Sanjay Gupta: Benefits of Vaccines Are a Matter of Fact,” CNN, January 10, 2017, https://www.cnn.com/2017/01/10/health/vaccines-sanjay-gupta.

↩︎ - “MMR Vaccine Does Not Cause Autism,” May 22, 2023, https://www.immunize.org/wp-content/uploads/catg.d/p4026.pdf.

↩︎ - Jeffrey P Baker, “Mercury, Vaccines, and Autism: One Controversy, Three Histories,” American Journal of Public Health 98, no. 2 (February 2008): 244–53.

↩︎ - “Thimerosal and Vaccines,” December 19, 2024, https://www.cdc.gov/vaccine-safety/about/thimerosal.html. ↩︎

- “Data and Statistics on Autism Spectrum Disorder,” May 16, 2024, https://www.cdc.gov/autism/data-research/index.html.

↩︎ - Mateusz P. Karowski et al., “Blood and Hair Aluminum Levels, Vaccine History, and Early Infant Development: A Cross-Sectional Study,” Academic Pediatrics 18, no. 2 (March 2018): 161–65.

↩︎ - Gilles Delage, “Rotavirus Vaccine Withdrawal in the United States: The Role of Postmarketing Surveillance,” Canadian Journal of Infectious Disease 11, no. 1 (January 2000): 10–12.

↩︎ - Janet R. Gilsdorf, “Hib Vaccines: Their Impact on Haemophilus Influenzae Type b Disease,” Journal of Infectious Disease 224, no. 12 Supplement 2 (September 30, 2021): S321–30.

↩︎ - “Autism Data Visualization Tool,” CDC National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities (NCBDDD) (blog), accessed March 24, 2025, https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/data/index.html.

↩︎ - “HPV Vaccination,” CDC Human Papillomavirus (HPV) (blog), August 20, 2024, https://www.cdc.gov/hpv/vaccines/index.html.

↩︎ - Poria Dorali, Haluk Damgacioglu, and Megan A. Clarke, “Cervical Cancer Mortality Among US Women Younger Than 25 Years, 1992-2021,” Journal of the American Medical Association 333, no. 2 (2025): 165–66.

↩︎ - Thomas Jay Oord, The Death of Omnipotence and Birth of Amipotence (Grasmere, ID: SacraSage, 2023), 122.

↩︎ - Andrew J Shattock et al., “Contribution of Vaccination to Improved Survival and Health: Modelling 50 Years of the Expanded Programme on Immunization,” The Lancet 403, no. 10441 (May 25, 2024): 2037–2316.

↩︎ - John Baron, The Life of Edward Jenner, M.D. (London: Henry Colburn, 1838), 295.

↩︎

image: flux forge ai

0 Comments